Dwelling – home – place: the cliff dwellings of the ancient Southwestern peoples strongly evoke these associations in most contemporary observers. How is it that the ruins of a civilization from 700 years ago resonate so intensely with us now, when our lives and our world in no way resemble theirs? The initial hook for me at Chaco was the plan – how the architectural order visible in that plan was riveting. But cliff dwellings appeal to normal people – not just architects – and this appeal comes from the image, not from the plan.

The first cliff dwelling I ever saw was Montezuma’s Castle (about an hour north of Phoenix), twenty years ago. It is the picture-perfect cliff dwelling, the small enclave for a few families, tucked into a small arch in a canyon wall. Different buildings have differently-colored masonry, so it is easy to imagine them as individual houses, rather than one large complex. Montezuma’s Castle is the dollhouse version of a cliff dwelling, the one a small child might draw.

The cliff dwelling itself is intriguing, and the surrounding environment is gorgeous. You are traveling in the high fringes of the Sonoran Desert, and you then descend into a narrow canyon of the Green River. The desert is replaced by an oasis – a lush riverbottom of grasslands and shrubs, with cottonwoods lining the river.

It is cool and green, sheltered from the sun and wind – it feels like a tended garden more than a natural environment. I think this is much of the appeal of cliff dwellings – humans belong here. While we may appreciate the stark beauty of the desert – mainly because we know we can escape it back to our civilized comforts at a moment’s notice – we know at a visceral level that it is not a place for us, that we couldn’t last a day there unsheltered. The desert inspires awe, a word which in its original usage was understood to include a dose of terror. The canyon evokes a sense of relief, shelter from the heat, a “place” in the trackless wastes of the desert, where humans can abide.

It is physical shelter due to the change in microclimate, but also psychic shelter due to the sense of enclosure. The horizon out on the desert can be a hundred miles away – here the canyon is just a few hundred yards wide, putting a boundary around the inhabitation that sets it off from the infinite spaces above.

You can also see the harmony between the natural world and the built world. The cliff dwelling is the accent which marks our fitting into this environment. JB Jackson defined landscape as the sum of the natural environment plus the built environment, and nowhere is this more archetypally visible than here. Humans haven’t dominated the place – they have recognized the qualities of the natural world which will nurture them, and have built a small dwelling which enhances their viability functionally. It has been done so perfectly that it is apparent to all on a deeply intuitive level. Tourists stand quietly, marveling at the ruins above them.

We returned there one winter when Greta was three years old, and she was fascinated by it, wandering along the river path and gazing up at the ruin. This year, as we approached Montezuma’s Castle again, I asked Greta whether she remembered it. She said she did, vaguely. But as we entered the canyon, specific spots triggered strong memories for her. The path paralleling the river by the cottonwoods, the opening in the woods approaching the cliff, the view of the houses themselves – they all came back to her as they appeared. This place had been so different from anything she’d seen in her short life that these vivid impressions had been filed away, ready to emerge when seen again. A little, primal human responding to the primal, archetypal elements

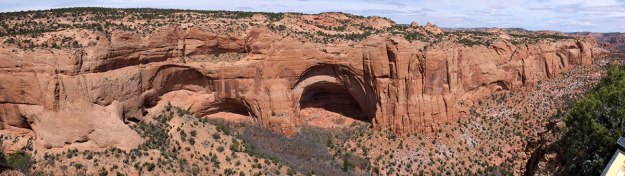

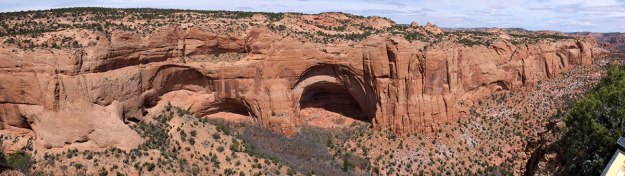

At Navajo National Monument we saw the remains of Betatakin from across the canyon. We weren’t allowed to enter the canyon, but even looking at it from above, the importance of the canyon microclimate was apparent.

As usual, the Park Service had an excellent sign explaining this – showing how the climate zones in a canyon were inverted from those seen on a mountainside, with the cooler weather, alpine vegetation at the bottom.

The village itself was tiny, tucked beneath the large arch across the canyon, exposed to the warming spring sun.

I started to wonder why we call these places cliff dwellings – canyon dwellings might be more accurate. They were never located on mountain cliffs looking across the desert, always in canyon walls.

The cliff-dwelling civilization followed the era that was centered at Chaco Canyon. A variety of reasons have been proposed for the change – the climate becoming more severe, with persistent drought requiring dispersal to locations with more reliable water supplies; attacks from other tribes leading to building more defensible villages; a breakdown in the social order, etc. No one knows the main reason, and some archaeologists think it is most likely a combination of many of these reasons.

The primacy of the canyon location became even more clear at Tsegi (Canyon de Chelly), where the Antelope House is located at the foot of a cliff, but on the canyon floor, not in a recess. We wondered about its risk of being flooded, but if the buildings have been there for hundreds of years, they must have called that one right.

Just as no one has the definitive reason as to why people left Chaco-era settlements, no one knows exactly why these villages were built in canyon cliffs. They have many advantages – shelter from the high summer sun while being exposed to the warming winter sun, easily defensible from attackers, always located with a good water source, where groundwater seeped out from cracks in the cliffs, overlooking a canyon bottom where crops could be grown, or slightly below the canyon rim, giving access to farmland above. Again, probably a combination of these reasons.

Access was Important – often from below as here at Mummy Cave at Tsegi. The “tower” form is apparent, although it is not known whether the tower function was critical, or whether it was just a vertical stack of rooms.

White Cliff House at Tsegi shows both ways the village on the canyon floor could be built – either in a arch above, or directly on the floor. There are a lot of these bottom-access villages at Tsegi – perhaps that meant that the canyon as a whole was defensible, and they didn’t have to rely on the inaccessibility of individual clusters.

(Tsegi was one of the most extraordinary places we visited – for many reasons beyond the cliff dwellings – so I will put up a post just about it.)

There are no cliff dwellings at the Grand Canyon – perhaps because it was just too big and deep to furnish the necessary microclimate that came with a smaller canyon. But there were ancient people there, dwelling in pit houses near the top of the rim. The Tusayan Museum has artifacts from this era thousands of years ago, including fetish animals made from reeds and willow twigs. They were simple and powerful, and again we northwesterners were astonished to see unrotted plant material that old.

We finally arrived at Mesa Verde, which was the center of the post-Chaco civilization. I knew some vague things about Mesa Verde before visiting, but I was unprepared for its extent. Within the Park boundaries, there are 4500 archaeological sites – cliff dwellings, pit-house villages, farms, and great houses which resemble those left behind at Chaco. It is only 100 miles from Chaco, but it is located in a very different environment, a series of branching canyons on a ridge of the Rocky Mountains, versus the desert plain at Chaco.

The most-visited ruin is Spruce Tree House, misnamed after the large trees which grew in front of and sheltered it, which were actually Douglas Firs (obvious to northwesterners). The pit house settlements at Mesa Verde were on the canyon rim, and the cliff villages are right below the rim, and accessed from above. Normally one can hike through this village, but a large piece of stone detached from the arch a little while ago, and so we couldn’t go in.

The Square Tower House.

The nearby Cliff Place is the largest of the villages. You can see the pattern of plazas and paths, square rooms (probably private or used for storage, as at Chaco), and the round rooms, which are now thought to be shared, living and working rooms, rather than just used as ceremonial kivas. There are square and round towers.

The most surprising experience was coming to this viewpoint and realizing how many cliff dwellings could be seen from one point – I have put yellow circles below the clusters, both above and below the rim.

This area comprises the Fire House and New Fire House to the left, with several other village in sight on the far canyon wall. Some of these are accessed from the rim, but the ones to the left also connect to the canyon floor, where it climbs higher.

Montezuma’s Castle is a relatively isolated village – certainly in communication with other villages, but alone in its own canyon. Mesa Verde is clearly an organized metropolitan area, with a system of villages and dwellings located at appropriate sites, all within close proximity. The Sun Temple is marked by the yellow dot just below the rim – it is a Chaco-style great house, and probably served as the center for all the villages in the area.

I began to wonder if the transition from Chaco to Mesa Verde might reflect some of the same processes that were seen in Europe in the Dark Ages. Did the environmental, social and political forces at the time make large, centralized settlements unsustainable, and so a smaller, decentralized village-based system sprang up? Or, closer to home, as some archaeologists have speculated that Chaco was the ancient version of Las Vegas, I wondered if Mesa Verde represents ancient sprawl?

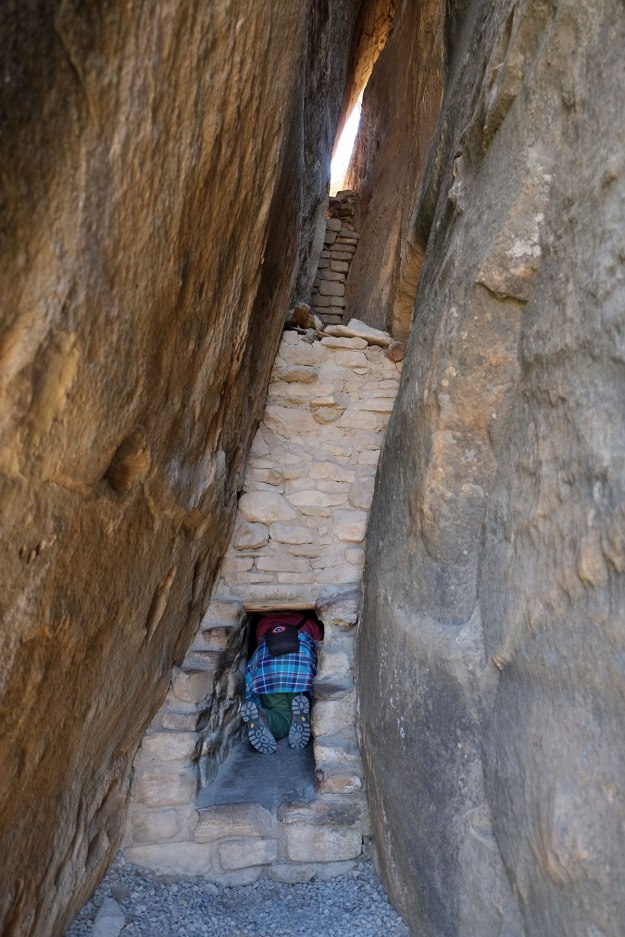

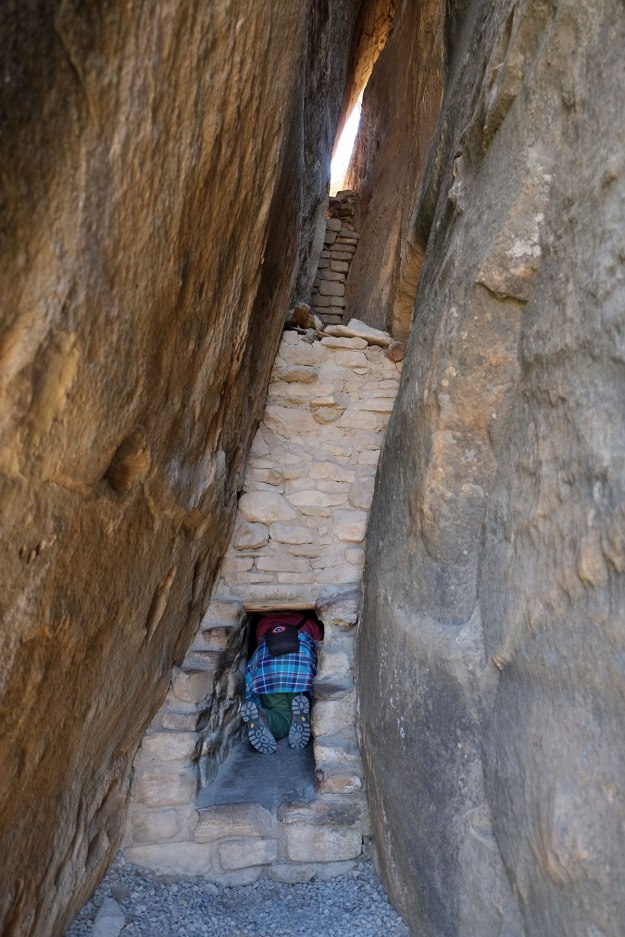

The most amazing thing at Mesa Verde is the chance to actually climb through a cliff dwelling. Unfortunately, three of the accessible villages only open after Memorial Day, but we were able to visit the Balcony House. We were part of a large group of tourists led by a ranger. When you buy your tickets, they are very explicit about the obstacles that you will encounter – after walking down metal stairs attached to the canyon wall for five stories, you hike along a path and approach a 32-foot tall ladder up to the village (marked in yellow on the right side of the photo below). When exiting the village, you have to climb through a 12-foot long tunnel/chamber, which at its tightest point is 18 inches wide and 27 inches high. Then you climb another ladder, up to footholds cut into the cliff, with a chain to hold onto and a steel fence to keep you from falling to your death (marked in yellow on the left side of the photo below). Given my claustrophobia and Greta’s fear of heights we carefully considered it, and decided we just couldn’t pass it up. When we joined out group, we thought that if we were worried, these people should have thought about it a lot more -there were quite a few typical American tourists, overweight and out of shape and very casually dressed (rock climbing in sandals?), and we wondered if some of them would actually be able to fit through the tunnel.

This is the first ladder, leading to the village:

We got past that fine, surrounded by people who were determinedly not looking down. Next was the narrow, defensible entryway.

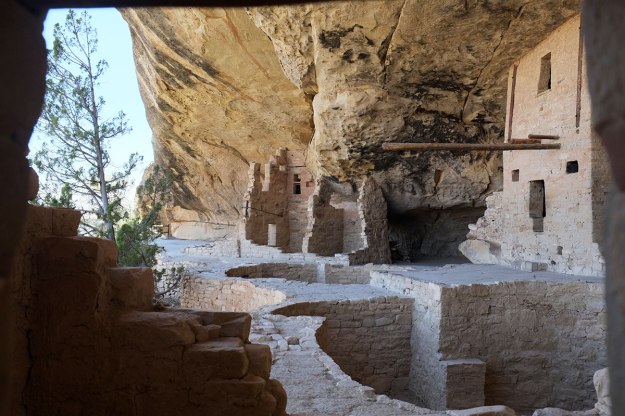

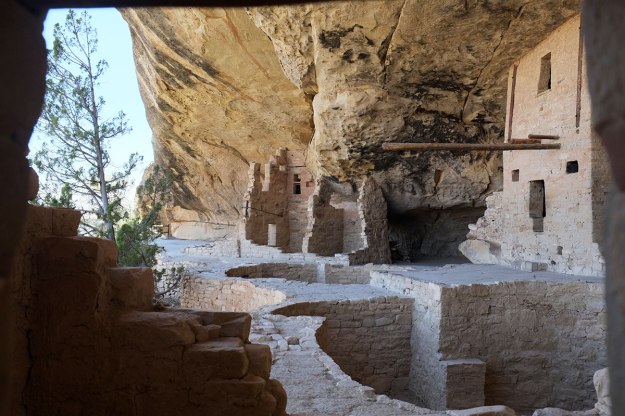

Which led to the first of two plazas – surrounded by buildings under the overhang on three sides, and open to the canyon to the east.

It was incredible to be standing there, knowing that 1000 years ago the residents had been right there, going about their business of grinding meal, cleaning animal carcasses, living normal lives. In the second courtyard, there is a large beam cantilevered out from a building – it is thought that this was used for hanging carcasses to dry, away from vermin (and res dogs).

The group is standing beside one of the round rooms in the plaza – entered from above, probably better heated due to its shape and location, and perhaps used for daily activities.

The view from the second plaza – across Soda Canyon. We don’t know if the Ancestral Puebloans appreciated views, but the modern Americans certainly did. Beyond the beauty, this picture points out another of the reasons we find cliff dwellings so meaningful – refuge and prospect. These factors probably come from a time in our evolution when they were critical to our survival – the knowledge that you were in a safe, protected spot, and able to see things coming from a ways off – either things you might eat, or things that might attack you. We may not have quite the same primal requirement for these conditions, but modern humans tend to really like places with these qualities. We wondered whether the Park Service might initiate some Air Bnb opportunities in their cliff dwellings.

The way out: it wasn’t a tunnel so much as a small chamber, with narrow deep doorways at each end. Here is 100-pound Greta squeezing through, and when I followed her I had to twist my torso to fit my shoulders through. We had made sure we were near the front of the line, as I had no desire to be in the middle when some large people got stuck ahead and behind me. Everyone made it through, but it was quite a while before some of them emerged.

This is looking down at the final ladder and the hewn footholds in the cliff. This was the most terrifying part for many people, and the camaraderie exhibited, as people in distress were exhorted and cheered on, was very commendable. We didn’t leave anyone behind.

The Southwest had many highlights for us – the landscapes and National Parks, the ancient ruins, some of the towns, the pueblos – and one of the best parts has been acquiring a rudimentary understanding on how all of this fits together. It is wholly different from where we have ever lived – climatically, culturally, historically – and by seeing these cliff dwellings within their environmental and historical context, it all started to make sense. 20 years ago I had visited the Hopi reservation, seeing villages that were, unimaginably, 700 years old. But now, seeing how humans have lived here through different eras even further in the past, the more recent settlements and cultures make more sense. There is an astounding, unbroken chain of people moving from somewhere else to construct the Chaco culture, then on to the cliff dwelling era, and then on to the pueblos, which remain into our time.