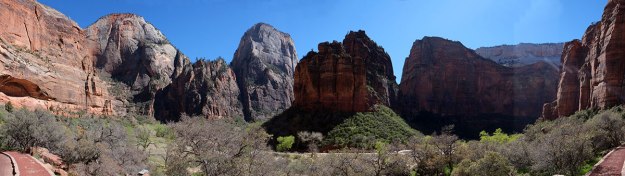

If South Dakota is the epicenter of kitsch, the Southwest is the center of the surreal. There are the surreal natural landscapes, such as Bryce and Antelope Canyons. There are the surreal sprawl-cities, such as Phoenix. And then there is Las Vegas, which is competing with Dubai to be the world capital of surreal architecture.

As a city, Las Vegas is just a smaller version of Phoenix – gridded sprawl, completely dependent on cars and air conditioning. From the air, Las Vegas is more comprehensible than Phoenix. Phoenix is so big that you get glimpses of parts, and have to assemble an understanding of the region in your mind. But the Las Vegas metro area has around 2 million inhabitants, and you can see the whole area dwarfed by the surrounding desert landscape. As in Phoenix, the visual contrast between the developed areas and the desert is vivid – nowhere can you see a better illustration of the power of our technology to dominate nature. These desert mega-cities are like space ships – life is possible, even enjoyable. But if the power goes off for a couple of days, everyone dies.  I would have liked to explore the mundane side of Las Vegas, which seems to be a sadder version of Phoenix, but I was traveling with a child who has spent her life in a small city in the Northwest, and so has almost no experience and even less tolerance of sprawl or traffic. So given how much Greta had hated driving around Phoenix, and the limited doses of architecture I could force upon her, we headed right for the Strip. She still whined, but I placated her with the promise of good food.

I would have liked to explore the mundane side of Las Vegas, which seems to be a sadder version of Phoenix, but I was traveling with a child who has spent her life in a small city in the Northwest, and so has almost no experience and even less tolerance of sprawl or traffic. So given how much Greta had hated driving around Phoenix, and the limited doses of architecture I could force upon her, we headed right for the Strip. She still whined, but I placated her with the promise of good food.

My one prior trip to Vegas had been at the tail end of my post-college cross-country drive with Norman and Dan. Norman and I had been camping out in the desert, and we detoured down the Strip, seeing the classic casinos and hotels of the 50s and 60s. It all seemed so horrible, tawdry and boring that we didn’t even stop – the contrast between the grandeur of the landscape and the cheesiness of the built environment was overpowering. (I had already heard Denise Scott Brown lecture on Learning from Las Vegas, and I figured that the drive-by was all the extra exposure I needed). We drove right out to Lake Mead and went for a swim, cleansing ourselves in the desert.

But as the nostalgia for Mid-Century Modern – even the kitsch of Las Vegas and Miami Beach – has swept us up in recent decades, I had come to retrospectively appreciate the stylistic qualities of this period. So we visited some of those classic casinos, such as the Tropicana, and were struck by their simplicity and clarity. They are glitzy (by the standards of their day), but they are also quite small, clearly laid-out, spatially interesting, and rather sedate, redolent of the longer attention spans of the pre-digital age. As one of my classmates (Alan Gerber) once described one of his own exuberant projects, It’s just the Maison Domino with special effects.

We visited other older casinos that were less elegant – I don’t even remember what this one was called – Camelot, or Dungeons and Dragons or whatever – that seems to be from the 80s. From the outside, bad cartoon buildings apparently made out of Legos.

On the inside, equally cheesy, coarse, inept and depressing. What Venturi and Scott Brown referred to as the Big Low Space. A cheap neutral shell smeared with a pastiche of banal allusions and signs, with the sole purpose of separating you from your money. The clear Modernist design of the older casinos was banished – if you knew where you were, you might leave and stop losing money, so the newer casinos became labyrinths of alcoholic confusion.  This is the Vegas I had imagined from countless TV shows and reading Fear and Loathing – a place where all the worst aspects of American mass culture are on exhibit – avarice, commercialized lust, emptiness, loneliness, superficiality. It had lost the cool of the classic Rat Pack era – the allure of sin was no longer elegant, it was just cheap and obvious.

This is the Vegas I had imagined from countless TV shows and reading Fear and Loathing – a place where all the worst aspects of American mass culture are on exhibit – avarice, commercialized lust, emptiness, loneliness, superficiality. It had lost the cool of the classic Rat Pack era – the allure of sin was no longer elegant, it was just cheap and obvious.

I had also heard rumors of the transformation of Vegas in the 90s – how it had become an upscaled family vacation destination, how the gambling was something you did after a day shopping, or at the pool with the kids. We arrived at Caesar’s Palace, a legendary resort which had apparently made this transformation. I expected to find it all howlingly kitschy, and one can indeed sneer at the craziness of hotel slabs cloaked in classical drag.

But I had to admit, it was masterfully done. These weren’t just blank boxes covered with ugly motifs, someone had actually drawn these facades and thought about proportion, hierarchy, detailing, and rhythm. On a warm March afternoon, the gardens were lovely. The vistas were extraordinary – seeing the copy of the Nike of Samothrace here is not quite the same as seeing it at the top of the stairs in the Louvre, but is its appropriation really that different from seeing it on axis at Wright’s Darwin D. Martin house? The designers may have been landscape architects, but even more importantly, they’d learned from movie set design. I felt that we were in Ben Hur, or a Star Wars prequel, or Game of Thrones. Obviously few of the visitors have been to the ruins of ancient civilizations; our “knowledge” of these eras is completely mediated by Hollywood, and the designers here were having a good time recreating this image in real, three-dimensional space. I began to wonder how much of it was naive, and how much archly self-conscious.

I got my answer around the corner. Near a busy plaza, where tourists were lining up for Grab-and-Go lunches, there was this quiet, off-axis statue. The subject matter is immediately obvious, if you happen to be paying attention to anything besides getting your next drink. It is the Death of Socrates (a copy of the work by Mark Antolkolski). I can just imagine the pleasure the designer must have derived from this subtle commentary on the culture swirling around it.

Nearby was a puzzling installation – a Buddhist shrine set in a Roman temple. I can only imagine that this is an accommodation of our global tourist culture. There are probably enough wealthy Japanese tourists coming here who might be confused or disoriented by the profusion of classical Western iconography, and who might be glad to see that people from their own culture are equally welcome to lose money in this unfamiliar venue.

We moved inside to the shopping concourse, and I was flabbergasted. It was absurd, it was ridiculous, it was bizarrely over-the-top, and I just loved it. Any architect who came of age in the Postmodern 80s (and especially one who had studied under Bob Stern), had to feel right at home and simultaneously be amazed by the incredible audacity of this, an appropriation of the language of the Roman Empire to serve the mercantile needs of the globalized web of corporate tourism and commerce. It captures the atmosphere of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas without needing the LSD. There continues to this day a dead-end branch of 1980s Postmodern Classicism, one that I thought mainly lived on in Eugene, but which I found alive and unwell in other architectural backwaters, such as in the deep South. It is usually a sad, ill-proportioned collection of disconnected references covering a mediocre building, the last refuge of the scoundrel architect. it exists at the level of sign, doing nothing to enhance one’s actual experience. (Bad architects can learn from Venturi too.) So to come to Las Vegas, and see it all handled magnificently was a complete shock. The scale of Roman streets and piazzi brought indoors to create scenography for the shopping mall. Astoundingly accurate elements and details rendered in God-knows-what materials. An evocation of the desert twilight in the superbly lit and painted trompe-l’oeil ceiling. If you want to build simulacra of classical Rome, this is the way to do it.

There continues to this day a dead-end branch of 1980s Postmodern Classicism, one that I thought mainly lived on in Eugene, but which I found alive and unwell in other architectural backwaters, such as in the deep South. It is usually a sad, ill-proportioned collection of disconnected references covering a mediocre building, the last refuge of the scoundrel architect. it exists at the level of sign, doing nothing to enhance one’s actual experience. (Bad architects can learn from Venturi too.) So to come to Las Vegas, and see it all handled magnificently was a complete shock. The scale of Roman streets and piazzi brought indoors to create scenography for the shopping mall. Astoundingly accurate elements and details rendered in God-knows-what materials. An evocation of the desert twilight in the superbly lit and painted trompe-l’oeil ceiling. If you want to build simulacra of classical Rome, this is the way to do it.

And as with Socrates outdoors, the irony continued. Certainly a PhD dissertation would be required to suss out all the layers of meaning in a Temple of Fendi, the God of Haute Couture.

In the hotel lobby, the collision of classical and contemporary culture continued. Classicial busts grafted onto bodies with Playboy busts.

Tutankhamen as a galley’s figurehead, heralding a cocktail bar. Look upon my drinks, ye Mighty, and despair!

The spatial sequence was exquisitely tuned – there were shopping corridors scaled as streets, punctuated with domed piazzi. Ceilings where Tiepolan perspective meets Pompeian painting motifs in a Pantheonic dome (that doesn’t leak), surrounded by a Corinthian colonnade with Roman fountain-derived caryatids inserted above the capitals, all bathed in an ethereal light.

I could have stayed for days, wandering this Postmodernist Xanadu, but the ticking clock of Greta’s attention span drew me back outdoors, away from the timeless world of the Caesars. As we moved through the transitions in place and time, we came across one final tableau that epitomized our return to the mundane world.

But not for long: we were immediately drawn into the Renaissance (and 19th-century descendant) fantasia of the Bellagio. The Galleria of Milan, complete with American tourists.

A hotel lobby with a massive installations of Chihulys, which seem to have achieved their apotheosis in this grandiose Baroque installation.

A porte-cochere worthy of the greatest Hummer limo that Vegas has to offer.

A magnificent palm court, that appears to be furnished in giant Japanese plastic toys designed by Jeff Koons.

By this point we were reeling from the juxtapositions of imagery and eras, as swoopy Hadidian forms competed with Venetian arches.

The strip itself was more lively than I expected, with hordes of tourists walking from attraction to attraction. I had thought that the hermetically-sealed atmosphere of the casino and mall – where the whole point is to keep the visitor disoriented in time and space – would be more dominant. But Vegas is not Disneyworld, a total environment controlled by one corporate entity. When you are within a casino complex, the experience is controlled to the nth degree, with every vista, movement and pause choreographed. But when you leave that world, you are out on a messy, noisy, exuberant street, where the “high” culture (or at least the expensive culture), meets the low culture.

There is the noted crazy variety in architectural and cultural reference, but there is also the juxtaposition of the fantastical with the everyday architecture of American life. In this way, it is actually like a city – where within the boundaries of property lines each owner decides what to build; there is no architectural review board in Las Vegas which demands that your new casino must respond to the style of the Tropicana next door. You may build the tasteful $1.1 billion City Center project, but someone will stick a standard sprawl-city CVS on the corner if you haven’t acquired that property.

I began to enjoy the madness of it all.

where no arresting idea, such as having the Eiffel Tower crash into an amalgam of Second Empire buildings, is ruled out.

The newest, and most different, addition to the Strip is the aforementioned City Center project, a 76-acre, 17 million sf, $1.1 billion, integrated mixed-use development, with hotels, casino, condos, retail and entertainment. Over the years I had heard about this project from the father of one of our recent grad students, who was the construction manager for the whole project. The scale of the undertaking was unbelievable – he had 250 people working for him in CM, coordinating with about 50 different design firms, and building at the rate of $30 million of construction per month.

It follows the model that everything within the property line is under the control of one entity, but rather than turning it all over to one of the firms that specializes in Vegas-scale development (firms of which you’ve never heard), a master plan was designed by Ehrenkrantz Eckstut Kuhn, and noted architects were hired to design each of the component buildings. These architects – including Gensler, Foster, Jahn, KPF, Pelli, Rockwell, Viñoly and Liebeskind – did something unique in Las Vegas – they designed buildings that look like buildings.

All prior buildings in Vegas really exist at two levels – there is the functional building, which is then overlaid with the exterior and interior design trappings that connote a historical epoch or style. They are essentially “romantic” buildings, depending upon association to derive their meaning. The City Center buildings are more “classical” buildings, manipulating the primary elements of architecture – space, light, movement, mass, materials – so that your understanding comes from the direct experience of those elements, rather than filtering that experience through prior associations. (Of course, this is what we think now; in the future, will people understand these buildings through their association with yet another historical style label, such as Decon architecture?)

The big urbanistic difference with the project is how it extends the depth of exterior space back from the Strip. With most casino complexes, there is a big porte-cochere and entry near the street, and the whole complex is essentially interior. But because this is such a deep lot, this car-entry zone is pulled into the middle of the block, creating a huge circle that feels more like an airport drop-off, which serves several buildings. It is a very grand space, beautifully detailed, and almost impossible to photograph.

The sleekness, tectonic expressiveness and minimalist opulence of the pieces show the increasing sophistication of the Las Vegas market. The well-done but still kitschy ambience of even the high-end, newer casinos of past decades appeals to the nouveau-riche, suburban middle classes: they may not understand serious cosmopolitan design, but they do see a difference between the older, cheap and tacky complexes, and the more expensively-built, “nicer”, elegant, extravagant projects. But if Las Vegas is to attract a clientele from the higher echelons of the globalized economy – say minor Russian oligarchs, Saudi princes or Chinese entrepreneurs – the architecture here must begin to exhibit the same degree of sophistication, and be designed by the same name architects, as they have seen in real cities, such as New York, London and Hong Kong. City Center represents the first attempt in Las Vegas to attract this market, with architecture that can be appreciated in a non-condescending, unironic way, by people with sophisticated and very expensive tastes. The emphasis in Las Vegas may be shifting away from the free drinks and buffet meals which supported the gambling middle class, to extremely high-end dining and (tax-free) shopping for the 1/10 of the 1%, who may begin to see Vegas real estate as a place to park some capital.

The interiors at City Center are striking, making much more use of daylighting and actual architectural elements than anywhere else in Vegas,

although the actual casino rooms are still variants on the Big Low Space. Casino designers know what aspects cause people to stay inside and gamble, and no architect is going to mess with that fundamental part of the financial equation.

The level of extravagance and Shiny Object detailing is amazing. This is a little cafe where we grabbed some gelato.

Perhaps the strangest part is a high-end shopping mall designed by Daniel Liebeskind. We became used to seeing his jagged buildings serving as museums and other cultural institutions over the past 15 years, and his style has become completely recognizable – you can spot a Liebeskind just as you can a Gehry or a Zaha Hadid. Often these spatial and formal special effects are said to represent our zeitgeist, to show how an artist has insight into the deep structure of our globalized culture and can embody those precepts in architectural form.

So to see the same forms used to house the likes of Prada and Vuitton is more than little bizarre at first. Do these forms have inherent meaning (I don’t think they really do), or have they just evolved into the latest hip visual vocabulary, one that will look as dated as bad Postmodernism in just a few years?

I think that when avant-garde architects are young (under 50), they push the theoretical underpinnings of their work to justify it, and to explain why none of it ever gets built. It is all revolutionary, and will undermine the civil as well as architectural edifice of our society, etc. Then when they are older and the visual culture has caught up with their aesthetic, they start getting work, and eventually end up designing shopping malls (just strange, jagged ones). I’m not sure that most of them ever really started with serious theoretical positions (architects tend to not be deep intellectuals, but rather, talented manipulators of three-dimensional reality), but even if they were, it is almost impossible to resist the temptation to actually build, and inevitably, any architectural movement that might have begun with a serious polemic and intentions just ends up as another style in the service of the globalized corporate hegemony.

There is a long history to this. Before the valorization of the avant-garde, architects saw themselves solidly within the power structure of a society, and knew their role in it. (HH Richardson once said, The first principle of architecture is to get the job.) But since Ruskin and the subsequent pretensions of the Modern movement to represent a moral as well as architectural critique of prior eras, architects have felt the need to cloak themselves in revolutionary rhetoric, which starts to sound pretty silly when they start designing shopping malls.

In my youth I worked for some firms that designed shopping malls and department stores, so once I got over the strangeness of this one being by Liebeskind, I was able to evaluate the shopping mall qua shopping mall. And on those terms, it’s a good one. The curving corridors allow you to see storefronts and signs ahead of you, rather than always to the side as you walk by. The big spatial nodes create destinations at the ends of the corridors, which in a traditional mall would be the locations of the anchor department stores. These large spaces then accommodate big inserted architectural elements, which are the bars and cafes. The high volumes give relief from the Big Low Spaces of the rest of Vegas, bringing in abundant daylight that makes strolling through the mall a pleasant experience. The architecture says, we don’t have to trick you into staying indoors and spending money, we assume that you are so rich that you just spend lots of money whenever you feel like it, and are used to doing this in a beautiful place. Frank Gehry went from being a straightforward mall architect to being Frank Gehry; maybe Daniel Liebeskind should try the reverse.

Las Vegas was like Texas for me – I had a lot more fun than I expected to. I thought all the pleasures would be snarky, slumming my way disdainfully through the cheesy excesses, getting into the Fear and Loathing mindset as much as I could with a 14-year-old in tow (I had learned how far that was at Mardi Gras). But the beauty of Las Vegas is that you can see larger currents in the global architectural and economic worlds writ large. There is not much subtlety here. Paradigms of different eras are juxtaposed, as are the aspirations of different strata of society. I had expected the complete unreality of the total fantasy environment, but evidence of the irresistible forces of global society were everywhere.

People go to Las Vegas as an escape, for a willing suspension of participation in the reality of the outside world of jobs, sprawl and daily life. I did the same – not gambling and drinking and going to shows, but allowing myself to experience it on its own terms, enjoying the architectural special effects and admiring the skill of those who created this artifice. But as we drove back out to our campground at Lake Mead, and once again contemplated that 150-drop in the water level, reality set back in. The high temperature in Las Vegas today will be 108 degrees. No one will be walking along the Strip. The parallels with the Roman Empire are more than architectural, and it’s hard to think that when Greta retraces this trip with her own kids in 30 or so years, that they will actually be able to visit Vegas.

It’s a wonderful spot, with people picnicking, kids turning somersaults, hikers resting their feet, and everyone looking up at the surrounding walls. The topography makes the place, and it has been carefully enhanced by subsequent interventions.

It’s a wonderful spot, with people picnicking, kids turning somersaults, hikers resting their feet, and everyone looking up at the surrounding walls. The topography makes the place, and it has been carefully enhanced by subsequent interventions.

We decided to do that, arrived the next morning, and were confronted with signs saying that a flash flood was “imminent”, and so we weren’t able to hike further through the Narrows.

We decided to do that, arrived the next morning, and were confronted with signs saying that a flash flood was “imminent”, and so we weren’t able to hike further through the Narrows.