The natural world and the ancient human world dominated our experience of the Southwest. The desert is almost empty of people, and those places where people have clustered – such as Phoenix and Las Vegas – were places we wanted to leave as quickly as possible, to head back into the vast spaces, silence and beauty of the desert. My friends Pam and Chuck once remarked, after their first trip through Oregon, that they were struck by the contrast between the incredible grandeur of the landscape, and the utter crap that had been built in it everywhere. I think this is true of the West as a whole, but Greta and I were more aware of it in the Southwest, as long residence in the Northwest had accustomed us to both its astounding landscapes and its crappy built environment. In the Southwest we were awed by the alien landscape, and able to see the tawdriness of the built landscape with new eyes.

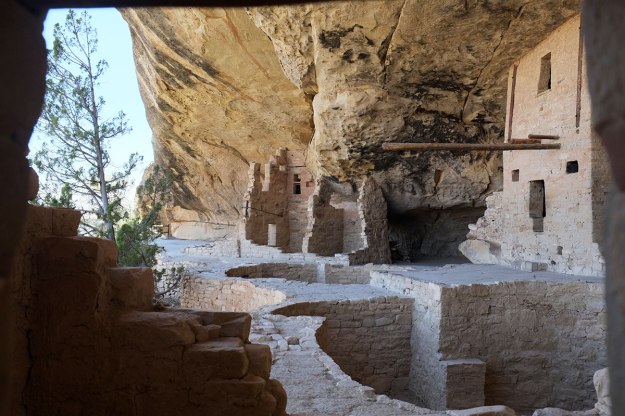

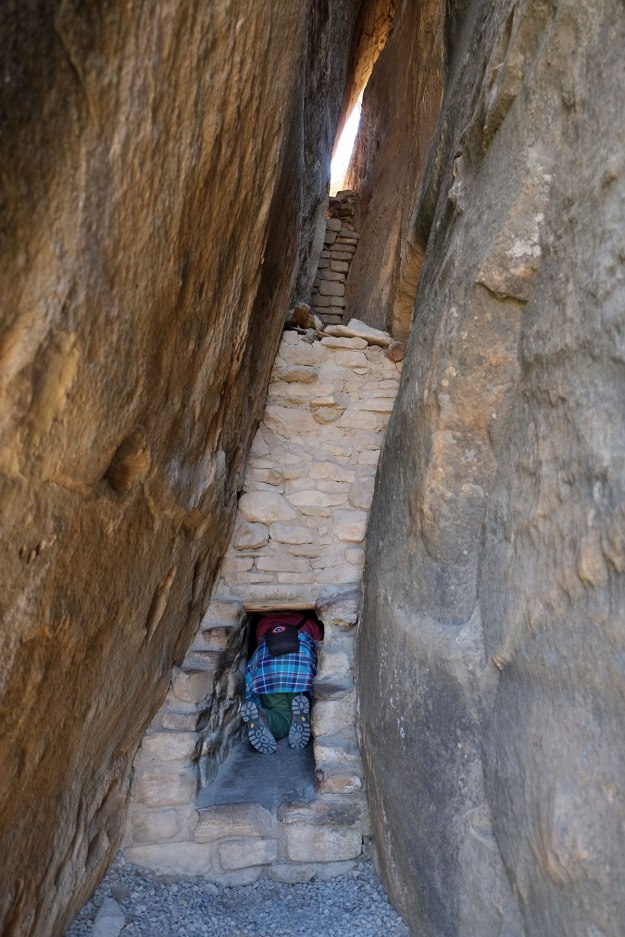

At a simplistic level, it appeared that everything natural was beautiful (or at least impressive), and everything we built was terrible. But the remains of the older civilizations countered this – they had the beauty of vernacular buildings, being of the local materials and responsive to the demands of the environment. They showed how humans could inhabit a place without destroying it, and by reconciling human needs with natural conditions, create a place that was even more meaningful to us than the natural world alone. Obviously there were recent human interventions that took care to work with this local context (Arcosanti and some buildings in Tucson came to mind from our recent travels), but we wondered about seeing places where recent human action actually enhanced our understanding of the world, as the primal qualities of cliff dwellings did.

This brought us to the artwork in the region – perhaps conscious interventions devoid of pragmatic considerations would show that people could comprehend the essential qualities of this place, and contribute to that understanding. Our first experience of this had been in Marfa, with Donald Judd’s work. Some of the work at the Chinati Foundation seemed disconnected from the place – object sculptures that could be understood on their own, that had just come to rest in that location. Other works seemed related to the built environment there – such as Judd’s aluminum boxes in the big artillery buildings, or Flavin’s installations in the series of barracks buildings. But other works connected directly to the landscape – most notably Judd’s 15 large concrete sculptures, out in the desert, creating an axis that terminated in a mountain.

After learning about the celestial alignments at Chaco, James Turrell’s Roden Crater came to mind, where he has been manipulating a volcanic mountain for decades, creating passages and rooms whose location and alignment enhance the experience of celestial and environmental events. But Turrell is still at work on Roden Crater, and it’s not open to the public. Then I realized that when we left Las Vegas, heading northeast towards Zion, Michael Heizer’s Double Negative would be only 20 miles or so off our route. I had always liked his sculpture at the IBM building in New York, and Double Negative struck me as the most spatially and topographically interesting of all the earth art from the 70s.

We put it on our itinerary, and one morning we rolled out of our Lake Mead campground, headed back to the desert to see big art and huge landscapes, and immediately got a flat tire on our trailer. This derailed our plans for half the day – changing the flat, and then driving into Vegas to find a tire store to buy a couple of spares. At one point, Greta looked over at me and observed that our one previous blowout on the trip had occurred in Alpine, Texas, as we were hurrying to Marfa for a tour of Donald Judd’s downtown compound. She wondered if there were some necessary connection between going to see conceptual art and blowing out tires. We discussed causation versus correlation, but it did seem weird that both times we had headed off to see art in the West, we had been thwarted. I regretted the lost opportunity, but it was just too late in the day to begin a long detour on desert dirt roads, and we headed off to Utah.

A month later, as we wound our way back west after two storm-caused changes of plans and directions, I realized one of our possible routes led back through Zion and Las Vegas, and we could attempt the Double Negative trip once more (and stop again at Oscar’s in Springdale, for lunch, which secured Greta’s buy-in). So north of Lake Mead we turned off the highway, headed down the Moapa Valley to Overton. Double Negative is hard to find – six miles out of town on a badly-marked road which winds through sparse residential settlement. We got to the end of the pavement, looked ahead at the rough dirt road and the steep slope onto Mormon Mesa, and left the trailer behind. The road was fine until we got to the route up the wall of the mesa, which we could see would be impassable if it were raining. But the clouds looked far off, so we drove up and across the mesa. We arrived at the cattle guard and turn-off for the last leg, and after 50 feet we turned the truck around, as the road was just too rough for a two-wheel drive pickup with normal tires. As we assessed the gathering clouds and assembled our gear for a hike, we heard the whine of motorcycles behind us. Images from all the bad biker movies I had ever seen came back to me, as they approached us in this isolated location, five miles out from civilization in the desert. It turned out to be three teenagers riding their dirt bikes out for an afternoon in the adjacent Virgin River Canyon, and as this probably-Mormon biker gang circled past us, we wondered if they would ply us with brochures and try to convert us.

We hiked the last mile or two, looking across the mesa to the distant mountains. It was an incredible, big landscape, seen from a mesa in the middle of a basin that was about 40 miles across. To the east the mesa dropped abruptly down to the Virgin River (the same river which runs through Zion), and there are a few short canyons which cut west into the mesa from this edge. Double Negative is at the head of one of these canyons. It comprises two sloping trenches, running north-south, aligned across the head of the canyon.

At the north and south ends, the trenches meet grade at the mesa top. The trenches slope down into the ground, until the side walls are 50-feet high. Walking along the side of a trench, you see it as a void, not perceiving just how deep it is. It could be relatively shallow, as here, or it could be a mile down, as at the Snake River Canyon – there is no way to tell until you walk right up to the edge.

As you walk down the slope to the flat bottom, your view is narrowed to just the perspective at the end of the slot, where you look across a flat area where the floor of the canyon has climbed up to that level, and across that, to the mouth of the opposite trench. The feeling of descent was much like what we had experienced at other canyons – you start on the rim, in the wide open spaces of the desert, but as soon as you go down past the rim, everything changes. You are in a bounded space – sometimes a mile across, sometimes 30 feet, as here.

The walls looked much like those of other canyons, with strata of sandstone and other rock types (just a little more regular).

I looked back at Greta, who wasn’t that interested in climbing down, as she thought the trench looked like prime snake territory. Outlined against the sky, the amount of erosion and collapse that had happened in the past 45 years was apparent. This trench is an artificial construction (or destruction), but then the natural forces take over. Boulders that were embedded in the ground are loosened and fall. The crisp edges of the cut become more irregular.

It is a man-made canyon, distinguished from natural canyons by its geometry (the meaningful contrast discussed by Marc Treib in his “Traces upon the Land” essay) but as the piece ages, this contrast will become less and less clear. Perhaps thousands of years in the future, archaeologists will discover these two aligned trenches, realize that they had been intentionally created, and ponder what their purpose might have been.

You emerge from the trench, turn 90 degrees, and are confronted by this view. The little canyon being traversed aligns with a prominent bend in the Virgin River, and with the highest peak in the mountains to the east. It is clear that this axis was critical in setting the location of the piece (why this particular canyon?), and the piece frames and emphasizes the view along the axis in a way that is invisible from the top of the mesa – the piece essentially establishes the axis, selecting this one perspective from the infinite number available from the mesa top.

The space in the middle between the two trench openings is an important place, and it clearly has attracted prior visitors, building their ritual fires.

Turning back towards the trench, the opening presents a powerful image for something so small.

It reminded me of the Santa Elena Canyon opening out to the desert in Big Bend, but there the canyon walls are 1500 feet high – how can a 50-foot high opening have a similar effect?

It may be due to the scalelessness of the desert – with the lack of markers of humans or trees, it is the form and not the size that we focus upon. As soon as you insert a person, the illusion is revealed.

Heading back up the trench the experience was even more dramatic, as the view through the gap was filled with sky and not with ground.

Back on the mesa top, the panoramic view reiterated the scale comparison. Double Negative is huge by the standards of art – 1500 feet long, 50 deep, 30 wide. But compared to anything else in this landscape, it is tiny. Trying to locate it in the aerial photos in Google Earth took a long time – two narrow shadows in alignment, in the middle of hundreds of square miles of desert.

Before we visited, I had appreciated the conceptual clarity of Double Negative. But like all good art, there was more to the piece than just the idea behind it. It is on the border between sculpture and landscape architecture, as the movement through it is essential to the experience. It engages and orders the larger landscape in a way I had never heard explained before. It engaged issues of scale and form, organic versus geometric, natural and built. At the time it was made, it pushed against the boundary of What Is Art – but that boundary has moved so far now that that the issue seems moot. The underlying ideas were strong, but the interaction of these ideas with the physical context was more powerful than I expected.

After this intellectual and aesthetic experience down in the trenches, I looked up to notice that the clouds that were looming earlier had gathered and headed our way, moving to the northeast against the wind. We hustled through this primal scene back to the truck, with lightning strikes getting closer and closer.

At the edge of the mesa we spotted our trailer out on the road,

drove back down the dirt road and headed south, crossing flash floods from the storm along the way.

The next day we left our Lake Mead campground again, and drove out into the Mojave Desert, where we blew out a tire on the truck.