After two months in the desert, it was hard to believe that this scene was real.

California is the mythic landscape of America. Before we are even conscious of it as a real place, its landscapes and views and cities are implanted in our brains through movies and television. It has been such a magical place in our mass culture for so long, and through so many different versions, that it’s sometimes hard to remember it is actual.

The first time I travelled to California was on the road trip with Norman and Dan after college. We drove down the Oregon coast and through Humboldt County (which is really Baja Oregon), then cut inland on 101 around the Lost Coast. At the first opportunity we got onto Highway 1, threaded our way through the coastal range (on what I can now reconfirm is indeed the twistiest highway in America), and returned to the Pacific Ocean, emerging from the hills and woods at this point:

I thought I was home. It was the most beautiful landscape I’d ever seen, even better than the imagery in the movies. Research in landscape preference has shown that for almost all people, no matter where they’re from, the two favorite landscape elements are water and savannah. Oregon had its awesome cliffs, but this landscape was more deeply appealing, a landscape where humans could imagine themselves dwelling, similar to the canyon oases in the desert. (Vancouver had a similar reaction to the landscape around Pt. Townsend on the Olympic Peninsula – the wild landscape seemed to embody the pastoral ideal, and was more welcoming than the alpine terrors of Desolation Sound.)

In later years, California maintained this magical aspect for me. I’d fly in from wintry New York on a business trip, and be met by friends in shirtsleeves who offered the options of wandering around San Francisco or driving up Mt. Tamalpais. When I moved to Oregon, suddenly California was just a day’s drive away, and I had some time to explore more of the vast landscape. Six years ago, Linda and Greta and I had spent two weeks of spring break driving around northern California, which was the best trip of my life, and the first time the then eight-year-old really got into travelling.

This landscape would be the penultimate destination on our trip this year – we had driven east until we ran into the Atlantic on Cape Cod, then south until we got to the Gulf of Mexico in southern Florida, then we were going to drive west until we hit the Pacific, at which point we’d turn north for home.

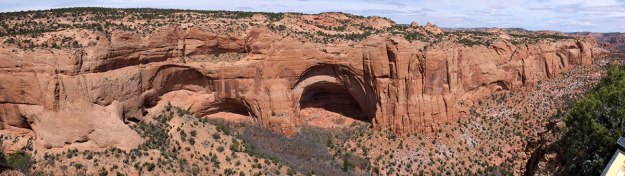

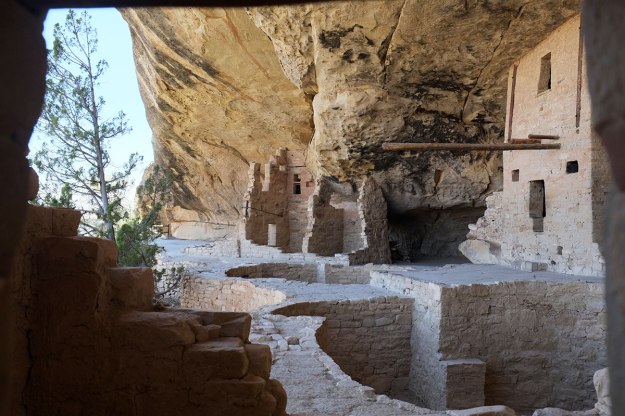

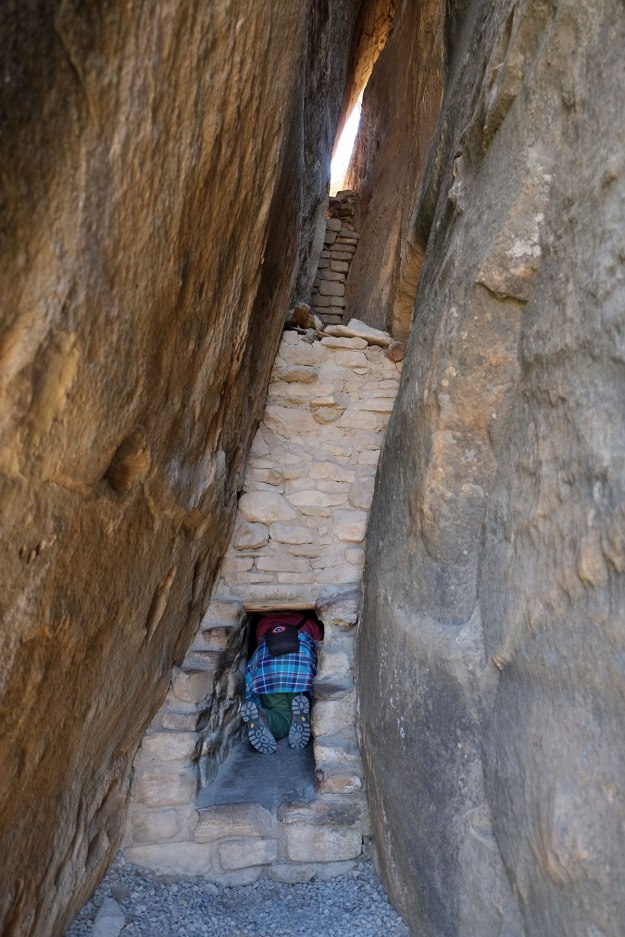

But first we had to get there. We didn’t finish our southwestern wanderings as we had originally anticipated, at Las Vegas – as we circled back and around, avoiding the wintry April weather on the Colorado Plateau, we’d ended up at Mesa Verde, 1000 miles from the Pacific. And while all our previous entries into California had been from an airport or from the north, this one meant driving across a succession of deserts almost all the way – a very different trajectory from which to approach California, but one that was probably closer to that of most historical visitors and migrants.

We plotted several routes, and had hoped to spend a little time in Death Valley, but the weather was already too hot in May, and with its proximity to the population centers of California, campgrounds had been booked solid way in advance. We also realized we had had enough desert for a while – we’d save Death Valley for a winter trip in a later year, when the ultimate desert experience could be better appreciated by soggy Oregonians. We tried to plot out an itinerary that would lead us by Sequoia and Yosemite, but the late winter conditions in the Sierras made that iffy, and the campground situation at Yosemite was even more ridiculous; our play-it-by-ear approach to this trip doesn’t mesh well with how most Americans plot out their vacations. So we chose a reasonably direct route west, one that would allow us to revisit some spots Greta had loved – the campground at Lake Powell with its jackrabbits, Oscar’s restaurant outside Zion – as well as some inevitable locations that are on no one’s bucket list, such as Bakersfield.

Things went well until we left Lake Mead to head into the Mojave Desert. We stopped for a bite in Primm, Nevada, which is really just a couple of casinos and an outlet mall located on the California border, a place so horrifying and soul-deadening that it makes you regret every decision you’ve made in your life that caused you to end up there.

Glad to be leaving this tawdry corner of Nevada, we slapped in the appropriate Joni Mitchell CD as we crossed the border, and entered the 36th state of our trip. We were in California, one of our favorite places, and there were giant solar collector farms on the side of the highway, harbingers of the progressive region where we belonged!

But once across the border, a different aspect of California emerged. We encountered the worst traffic jam of the whole trip, 100 miles of bumper-to-bumper driving across the Mojave, until Barstow, where the Angelenos turned south to go home. (When we eventually reached San Luis Obispo, Brian paled when he heard that we’d tried to drive west from Las Vegas on a Sunday afternoon.) We continued towards Bakersfield on Route 58, in a semi-industrialized desert landscape (mines and air bases) that rivaled the west Texas area around Pecos for Most Unpleasant Landscape of the trip. Then twelve miles west of Boron, we blew a tire on the truck (doubtless caused by the residual minimalist art juju from seeing Double Negative the day before). I changed the tire only to discover that the spare was too low on air to use, so we spent a couple of hours making phone calls, finally convincing some guys from a tire store to drive out and pump it up for us. We limped into Bakersfield quite late.

The next morning, I stepped out of the trailer right next to a rotting orange on the ground. I was surprised to see this garbage in what had seemed to be a rather well-groomed campground. Then as I walked to the bathroom, I spotted more oranges lying around. I looked up, and realized the campground was in an orange grove. In the dark we had crossed out of the Mojave and into the Central Valley, one of the places where human intention has had the most extreme effect upon the environment, turning an arid valley into the major food-producing region of the country. We knew that this was an artificial creation, and the Central Valley was on our checklist for the Climate Change Farewell Tour, as in the next century it will most likely be radically transformed by aquifer salinization, mega-drought and climate change. But at that moment, after two months in the arid Southwest, the orange grove looked pretty good.

We drove under I-5, and realized we’d hit the bail-out point – for the first time in eight months, if we wanted to head home, it was just one long day’s drive away. We spent the morning driving through the agricultural area, vast orchards of almond trees, and some of the strangest buildings we’d seen.

The highway climbed out of the valley, passing through a low-level petro-landscape (another part of California we lose sight of). The only other vehicles we passed were white pickups driven by guys working for oil or utility companies.

Finally, in the distance we could see hills covered with grasslands,

After the jagged slickrock canyons of the Southwest, this valley of gentle hills with grazing cattle was surreal – it looked like an illustration in a children’s book. Coming out of the desert, even this semi-arid landscape felt lush, a place where you could let down your guard and not worry that the environment had it in for you personally. We wondered about the feelings of the migrants coming into California this way, the Dust Bowl refugees spotting the first sign of the coast that lay ahead.

We crossed the hills into San Luis Obispo, and the next day Brian and Karen drove us to the Pacific. At Montaña de Oro State Park, we reached the ocean,

and explored on a beach covered with small rocks which had had holes bored in them by piddocks , and which Greta realized would make excellent necklaces.

At Morro Bay, our first glimpse of the misty, overcast coast. It seemed so familiar to us, and we realized that coming home is a series of recognitions. We are so used to airplanes – where we travel great distances and pop out into a different world – that we think of returning as something that happens all at once. But when you travel great distances on land at a slower speed, there are incremental changes in the environment, each of which triggers a reaction, filling in pieces of the picture that you eventually recognize as home. Even though we were still 1100 miles from Eugene, this was the first place in eight months that fell within the outer circle of home, the first place that we felt was ours.

After a few days we headed north, to the elephant seal beach at San Simeon. Sea mammals, another familiar piece – although there were a lot more of them and they were all much bigger than we are used to in the Northwest.

Big Sur, on an overcast day, had a different quality than we’d experienced on previous trips, but still astounding. After the washboard dirt roads of the Southwest, seeing such a smooth asphalt highway built in such impossible terrain was incredible; this must be a very rich place, we thought. We had just spent so much time in spectacular southwestern desert landscapes that we had a heightened awareness of both the contrasts and similarities – the landforms, the scale, the water, the sky, the vegetation, the humidity, the road itself. We wondered what the Hopi teenager we had met would make of this.

And at the end of Big Sur, the beach at Carmel. With the absence of cliffs, we were able to recognize this place as the antithesis of the southwestern desert in every way. Our acclimatization for the past week had been gradual, but here it hit us with full force. This was the promised land at the end of the road. Greta and I just sat and stared, not quite able to process the reality, beauty and meaning of such a place. Rob Peña and I used to talk about whether you could ever feel truly at home in a landscape that was completely unlike that where you had grown up, whether certain landscapes were imprinted on your brain. As he had grown up in Los Alamos, he feels at home in the Southwest in a way we never can. Greta and I had loved the desert, but it could only ever be as a visitor – it would never feel like home to us. Although I had grown up in the Northeast, there were enough common elements here – ocean, sky, beach, trees – that it felt familiar, and for Greta it was even closer to her ideal (although perhaps a bit too sunny).

We luxuriated in this benign environment, where the local wildlife isn’t something that can kill you, but instead is happy to pose for a photo. There’s a reason why California is the fabled land of America, why it was irresistible to so many people in the past century; we were almost giddy with its attractiveness. We wondered why, if this place actually exists, people live in places like Phoenix instead of here. And then we looked around Carmel and said, Oh yeah, you can’t afford to live here.

Their eyes only added to the alien qualities, W-shaped pupils observing us as they wait patiently for the takeover.

Their eyes only added to the alien qualities, W-shaped pupils observing us as they wait patiently for the takeover.  Flashing patterns can be used for communication, as well as hiding from predators andstunning potential prey, so it isn’t unreasonable to assume that cephalopods have an ocean-spanning network of spies and soldiers waiting to swarm into our cities when they flood.The most interesting things in the world are often also some of the scariest, and these ancient, plotting, shapeshifting buglers who can grow to enormous sizes are no exception. It’s no wonder to me that sailors feared the Kraken.

Flashing patterns can be used for communication, as well as hiding from predators andstunning potential prey, so it isn’t unreasonable to assume that cephalopods have an ocean-spanning network of spies and soldiers waiting to swarm into our cities when they flood.The most interesting things in the world are often also some of the scariest, and these ancient, plotting, shapeshifting buglers who can grow to enormous sizes are no exception. It’s no wonder to me that sailors feared the Kraken.