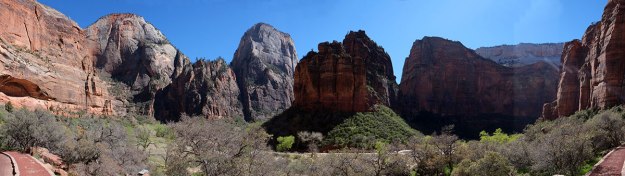

The garden in the desert – the defined place that is lush and life-sustaining in the middle of infinite, awesome emptiness. We came across these intermittently in our travels in the Southwest, and in each one we felt a sense of shelter, relief, of coming back to a world that nourished humans. Santa Elena Canyon, Montezuma’s Castle, Zion Canyon – they each had their extraordinary scenic appeal, but the experience of them is more than just visual, and is heightened by the contrast with the world outside their confines. Tsegi (Canyon de Chelly) may be the most enticing of them all. It has the grand vistas of the others, but it also feels the most inviting – a green world at the bottom of a 20-mile long canyon, not just a small interruption in the desert.

The garden in the desert – the defined place that is lush and life-sustaining in the middle of infinite, awesome emptiness. We came across these intermittently in our travels in the Southwest, and in each one we felt a sense of shelter, relief, of coming back to a world that nourished humans. Santa Elena Canyon, Montezuma’s Castle, Zion Canyon – they each had their extraordinary scenic appeal, but the experience of them is more than just visual, and is heightened by the contrast with the world outside their confines. Tsegi (Canyon de Chelly) may be the most enticing of them all. It has the grand vistas of the others, but it also feels the most inviting – a green world at the bottom of a 20-mile long canyon, not just a small interruption in the desert.

We dropped our trailer in the Cottonwood campground, (run by the Navajo parks service, complete with res dogs), and drove up the north rim to the Antelope House overlook (which actually is looks down into Canyon del Muerto, one of the two large canyons in the National Monument.) We looked down from on top of the sheer red rock cliffs to where they crash into a green meadow below – a continuous carpet of grass and shrubs, not just some straggly desert survivors. Then we heard a faint rumbling sound and saw movement – a herd of horses galloping down a dirt track, and turning into a field below us.

After the visually inanimate desert, where wildlife is sparse and well-hidden from our view, this scene was incredibly affecting, primal, almost Edenic – beautiful animals running through a green landscape. A high-pitched, whining sound arose, and then we saw the source – two Navajo cowboys on motorbikes herding the horses – so not completely Edenic.

This is the one oasis canyon where you don’t have to imagine people living there – people actually do live here, and have for 5000 years. First there were small groups, then the Ancestral Puebloans arrived over 1000 years ago and built cliff dwellings. After they moved on to the modern pueblos, the Hopi would still return here for summer hunting and farming. Finally, the Navajo arrived a few hundred years ago, and have lived here ever since.

An etymological digression, which travel in the Southwest seems to frequently require: I had always wondered how this place came to be called Canyon de Chelly (pronounced “shay”) – a strange not-Spanish, not-French hybrid. It turns out that it is simply a corruption of the Navajo word Tsegi, (pronounced Tsay-yi), which roughly means canyon. So Canyon de Chelly means Canyon of Canyon, which is really quite a stupid translation when you think about it. Since we now live in an age where we increasingly recognize the original native names for places (such as Denali), and sometimes officially change the names back, I’d like to move Tsegi to the top of that list.

Tsegi is a centrally important place to the Navajo – I’ve seen it referred to as the heart of the nation. It is a US National Monument, but it is jointly administered by the National Park Service and the Navajo nation. Most of the land is private, and it is all under Navajo jurisdiction; we weren’t sitting around the campfire at night drinking bourbon while on the res.

You can see the difference in preferred settlement patterns between the Puebloans and the Navajo quite clearly, even in this confined canyon. The Hopi and other Puebloans (descendants of cliff-dwellers) live in dense villages, clustering together in one spot in the desert. The Navajo prefer open country, and don’t seem to appreciate towns – their cities all seem to be recent service centers, places where the 150,000 members of their nation can get supplies and intersect with the modern world of bureaucracy. They take the normal nature/built-world Manichaeism typical of the Southwest to the nth degree – Navajo empty-nesters and millennials are not flocking to walkable neighborhoods. Everywhere we went in this vast reservation, this was the typical dwelling – a cluster of small buildings, surrounded by range land, where they raise their herds of sheep:

Even within the confines of Tsegi, this is the normal pattern – individual farms and ranches spread up the lengths of the two main canyons, connected by dirt roads, which sometimes are coincident with the streams that run through them. Since the land is private, tourists are not allowed to wander at will. There are drives along the north and south rims that give access to major overlooks. If you want to visit the bottom of the canyon, you must hire a Navajo guide, who will take you through either in a jeep or on horseback. There is one point where you can hike to the bottom of the canyon from the rim, which might be the most fascinating hike we did on this whole trip.

At Antelope House overlook, we watched the herd of horses until they were out of sight, then we turned to Antelope House itself, a cliff dwelling on the canyon floor, below the cliff.

No one would be coming down that cliff (to the right in the picture below) and since the only way in is at the mouth of the canyon, 5 miles away, an integrated defense of the whole canyon might have made sense, rather than counting upon the inaccessibility of each individual cliff village.

It is an extraordinary spot, where Black Rock Canyon splits off from Canyon del Muerto. The escarpment in the middle below is Navajo Fortress, a well-hidden and completely defensible spot to which the Navajo warriors could retreat in their wars with the Spanish and Americans.

On the south rim drive, looking into Canyon de Chelly, we caught a glimpse of riders on the road / streambed.

The Tsegi overlook affords a big-picture view of the canyon.

The end of the drive is at Spider Rock, an 800-foot butte which is the home of a legendary spider, used in tales to frighten Navajo children. The Chuska Mountains are visible in the distance.

We stopped at other points, with equally cool vistas of canyons or other cliff dwellings. But as always with us, the best way to see and understand the place was to do what hiking we could. So we headed for the one trail down, which leads to the White House cliff dwelling. The path winds its way down the cliff, with switchbacks and a couple of tunnels.

Your perspective always changes (literally) as soon as you’re below the rim – you’re below the horizon, rather than above – in a space enclosed by the canyon walls, not just looking down into it.

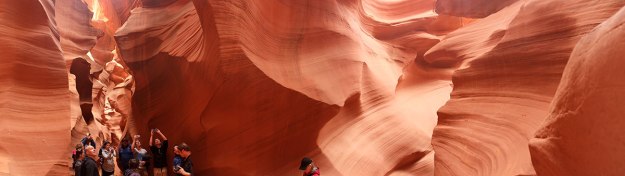

There were the big views out into the landscape, and closer views of astoundingly textured rock walls. With our fundamental lack of interest in the details of geology, we could only float hypotheses. Perhaps this formation is somewhat similar to Antelope Canyon, just not as smooth?

And as elsewhere at Tsegi, there is the astounding contrast between the red rock walls, and the river course with the cottonwoods putting out new leaves.

The view through the last tunnel was astounding. It reminded me of the entrance to Prospect Park from Grand Army Plaza, where there is a view through a tunnel under the roadway to the slope beyond, with one tree in the foreground. Did the Navajo hire Olmsted to place that tree here? (He probably would have moved it off-axis.)

On reaching the bottom, the trail runs along the river, with the horses as the perfect scale figures in the landscape. This is what makes Tsegi different from all other places in the Southwest – the pastoral. Whereas most of the Southwest is beautiful for its awe-some qualities – the sense that untamed nature dwarfs us and our puny human sensibilities, and a few places are appealing because we think humans could actually survive here for more than a day – Tsegi is an inhabited landscape. We can see evidence of human habitation through time and into the present, and we have the stark contrast between the horses calmly grazing against the sheer cliff behind.

This contrast between the hard, barren cliffs and the life in the canyon plays out with the vegetation too. We were there in April as the bright-green leaves of the cottonwoods popped out. Living in the Northwest, cottonwoods are just one of the many trees we know, and we notice them mainly when they cover the bikepath along the Willamette with their seed pods; after a spring in the Southwest, I will never take them for granted again.

The trail arrives at the White House cliff dwelling – somewhat hidden behind the second cottonwood from the right.

By this point we had seen several cliff dwellings and thought we comprehended them – not in the sense of completely understanding their history or context, but in the way in which they resonate with us modern humans – the way that they so perfectly embody the idea of dwelling: some primal neural pathway fires and we instantly and deeply feel the rightness of people living in these places, understanding them as our ancestors, across centuries of wild development. But seeing White House brings this to another level. The inhuman immensity, the outward sweep of the cliff above, poised over the tiniest marker of inhabitation. The recognition that within this astounding and hostile natural world, humans somehow made a place for themselves in a way that was not just about survival, but seems to embody the deep meaning of our place in that world.

We just sat and stared for quite a while, then wandered around the area, looking back at the White House from different perspectives. It was like seeing any great work of art – there is the instantaneous apprehension of its impact, but then you have to slowly consider it, let the levels of meaning sink in. It is a restful and quiet place – a couple of Navajos selling crafts, a jeep arriving with a family of tourists, a small herd of horses wandering by – but mostly there is the contemplation of the village, the cliffs, the river, the trees, the birds (and snakes). You just come face to face here with the history of the human species, making a place for themselves in this often harsh, yet beautiful world.