Back in the 1970s, there was an explosion of research and innovation in energy-efficient and solar building. It largely disappeared in the 1980s – partially due to the lack of support under the Reagan administration, but also because it had focussed almost exclusively on building performance, neglecting the many other factors (included in firmness, commodity and delight) that motivate humans in their building preferences and decisions.

We’ve come a long way since then, and the Brock Environmental Center exemplifies how the new generation of high-performance buildings are not just machines for saving the earth in, but buildings that satisfy the full range of human needs. The goal of making a very high-performance green building isn’t in conflict with making good architecture; this building shows how those performance-oriented features can fundamentally enhance the quality of the architecture overall.

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation is a multi-state nonprofit, dedicated to saving Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. They have a history of making buildings that embody their environmental goals – their Philip Merrill Environmental Center in Annapolis was the first LEED Platinum building in 2001. They have recently followed this with their Brock Environmental Center in Virginia Beach, which is on track to be certified as LEED Platinum, plus meeting the even more stringent requirements of the Living Building Challenge. Both of these buildings were designed by the SmithGroupJJR.

The context of the site, both local and regional, is critical to understanding the meaning of this building. We arrived in Virginia Beach in early December, not fully realizing how it was our first exposure to the environment in which we’d spend most of the next two months – the edge where the great Southern coastal plain meets the sea. We descended from the Piedmont around Charlottesville into this plain, which is extremely flat, with fairly monotonous pine forests and shallow broad rivers with very little fall in elevation, which widen out into enormous bays that join the sea. The mouth of the Chesapeake is one of the largest, opening to the Atlantic in the Norfolk-Portsmouth-Newport News-Virgina Beach metro area. The beaches are wide and beautiful, and in many places are protected by constantly shifting barrier islands (although not here).

Behind this beach and a narrow band of development is First Landing State Park, which preserves about 3000 acres of the Lynnhaven River estuary where it joins Chesapeake Bay. There is lots of low-lying salt marsh,

plus some uplands with pines and live oaks, and Spanish moss everywhere.

The Pleasure House Point parcel (about two miles from the park) which houses the Brock Center site was slated for residential development, but after the Crash it was purchased for recreation and the preservation of its wetlands, salt marsh and meadow, and maritime forest. The building sits on a small upland site, not encroaching on the estuary.

The parti of the building is simple – a narrow, curving linear scheme, raised a tall story above the ground plane. The more public lobby and meeting rooms are at the top of the ramp:

The lobby shows the tectonics of the building, with structure and mechanicals exposed within the simple shell:

the curving corridor along the southern exposure

which has a porch / shading device running its length.

a panorama of the open office space – glazed doors from the corridor on to the porch, balancing glazing to the north, and clerestory lights facing both ways.

I won’t go into great detail about the all strategies employed in achieving Living Building Challenges goals – as the architects do a very thorough job of that on this webpage:

http://www.cbf.org/about-cbf/offices-operations/brock-center-about/making-of-a-green-building

The Brock most resembles a laboratory in its form and organization: a simple, open shell, which can accommodate a complex array of mechanical systems and human uses. This division between the architectural elements and the mechanical ones leads to a building which is conceptually clear, tectonically articulate, and very efficient. The architectural elements are manipulated to achieve as high a level of passive energy performance as possible. The section is optimized for daylighting, minimizing heat gain, and enhancing natural ventilation. This leads to habitable rooms which are commodious, tall, well-lit and very comfortable. The need for south-side shading lead to a wonderful porch, something not many office buildings have. The energy performance may have driven the scheme, but the elegant resolution of these demands produced very fine spaces.

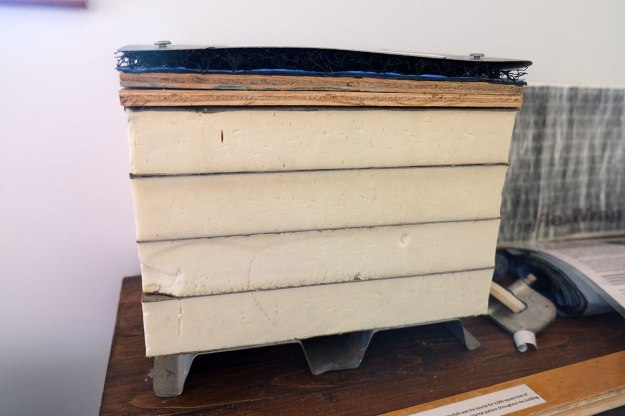

Passive strategies take you as far as they can, but have to be supplemented by active ones, especially in a hot, humid climate. The systems employed in the Brock are sophisticated, and in some cases, unprecedented. The insulation levels of the envelope are obvious (they have annotated pieces of their materials on display throughout the building). For mechanical heating and cooling, there is a ground-source heat pump. For electrical needs, there is both rooftop PV and a couple of wind turbines, which are producing more power than needed on site.

And for all you ASHRAE geeks reading this, the water and waste systems are extraordinary. All toilets are composting, using the Clivus Multrum system, leading to containers at the lower level. The limited amount of blackwater effluent from the tanks is trucked offsite. As the toilets are located in different parts of the building and some see more usage based upon location, there was an initiative during the first year to get occupants to vary which toilets they used, to spread it around, so to speak.

The building’s greywater is run through various biofiltration systems and delivered to raised-bed planters on the grounds. But the most innovative system is for the rainwater, which is collected, filtered, and used for th building’s domestic water needs. This is the first commercial building in the US to achieve this legally. The various gutter leaders connect below the main floor level:

and there are lots of pumps and tanks and filters and controls which I won’t pretend I understand:

But the implications for the architecture are obvious, and led to a clear design protocol. Make simple envelopes which can be optimized for passive performance. Design to accommodate extremely sophisticated active mechanical systems, which may change over time. Complex machines in simple buildings.

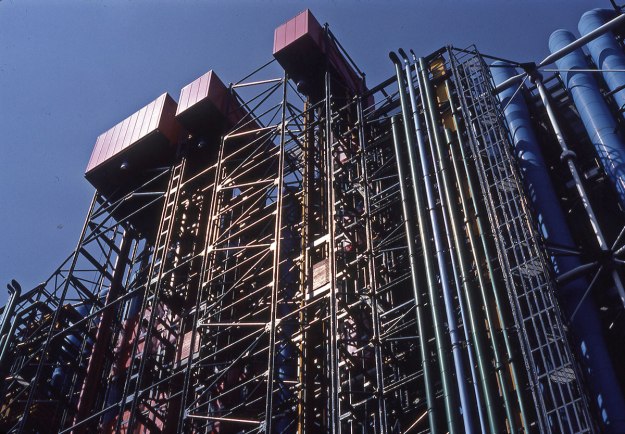

Buildings such as this may rationally resolve an argument that has been going on for a few decades. Back in the 60s, buildings such as the Beaubourg made the expression of the building’s systems – both structural and mechanical – the basis for the parti. While there was certainly a conscious attempt to integrate these systems into an overall composition, it wasn’t obvious to laypeople.

Architects such as Lou Kahn also articulated the necessary elements of the building, but more explicitly integrated them into the buildings overall design intention, such as at the British Art Center.

Postmodern architects reacted against this direction. I remember Bob Stern making the case that the British Art Center was irrational at its core: it expressed the mechanical systems, but by making them part of the formal design, it forced them to serve aesthetic goals rather than engineering ones; in doing this, it increased their cost and inefficiency incredibly, so that what you are seeing is not so much a rationalized mechanical system but a very expensive expression of the idea of a mechanical system. Stern asked if we had any idea how much a round stainless steel duct cost, and argued that if you wanted an efficient, cost-effective building, you should design the spaces you want for human habitation, build them out of steel studs and gypsum board, and leave lots of spaces between where the engineers can put all the mechanical equipment they want, without having to worry about making it beautiful.

The Brock Center shows a clear, rational compromise between these two positions. The architecture can be what it wants to be, but based upon performance factors along with goals for human habitation. The building systems are exposed where it makes sense – steel structure, ductwork, piping, sprinklers, conduit – but not everything is dogmatically expressed. A main rainwater collection tank is openly placed near the entry ramp,

but they made the wise decision to keep the composting toilet tanks in the mechanical room, out of sight, where they can do their work efficiently without offending delicate sensibilities.

Perhaps the key is recognizing the messy, often compromised reality of a building. Achieving extreme simplicity of appearance requires extraordinary hidden complexity (which is very common in high style buildings right now), whereas letting the purely functional and efficiency-driven goals drive the design is unlikely to produce a satisfying building on other levels. The Brock Center is a straightforward, elegant solution which integrates many of the issues, not compromising on performance for aesthetic reasons, but also not forgetting that buildings are for people and not just solving technical problems.

And as we design for sensitive coastal environments and the anticipated sea level rise with climate change, for the first time I start to appreciate buildings set up on piloti. Corbu was 100 years ahead of his time, and he didn’t even know why.

Thanks for writing that article! I was the project designer for Brock, and the project architect for the Merrill Center. Both buildings are deceptively simple, but given the complexities and sophisticated systems involved to achieve net-zero, composing it all into a straight-forward, clear architecture that orients the visitor while always maintaining focus toward the Bay and the site… can be tricky.

LikeLike

Greg – glad you liked the post! It is an excellent building, mainly for exactly the reason you mention – achieving these performance goals while making a beautiful, clear building. This will definitely become one of the case studies I use to show my students what is possible. Cheers!

LikeLike

feel free to reach out to me, or have students reach out to me, if they are looking for more info about Brock. greg.mella@smithgroupjjr.com

LikeLike

Thanks very much – I’m sure we’ll do this – but not until I get back to Euegne and start teaching again next year!

LikeLike

Great place, the landscape of the intercoastal waterway is amazing, we were impressed when we were there it was very beautiful. Interesting buildings but they would have been better if the architects would have learned from the local vernacular and use a form language that seemed more sympathetic to the region. That said, cool that it has so much high tech stuff in it to achieve a high performance, I actually don’t like them very much….

LikeLike

I have never been to this place, but I am from Virginia Beach!! I’m enjoying following along and glad you made it to my home. Wish I’d caught you in time to send you to my favorite place of all time, Regino’s Pizza in Norfolk. Any chance you got to Nags Head, North Carolina? It’s another one of my favorite beaches. Please say hi to Greta from Keefe. Cheers!

P.S. Since I’m a lover of Southern fare, I’m especially enjoying Greta’s food posts. I loved the ones about BBQ and hush puppies!!

LikeLike

Sorry we missed the pizza, but we were moving into our seafood and bbq period! Didn’t get to Nags Head this trip, but we had been there before as my sister used to own a house on the Outer Banks. Hi to Keefe from Grata, glad you’re liking the blog! Greta will have another food post up soon, as we have been eating mighty well in New Orleans. Cheers!

LikeLike